Dr. Krystyn Moon covered the history of racial discrimination in housing in Northern Virginia. Photo by Glenda Booth

Courtesy of Krystyn Moon

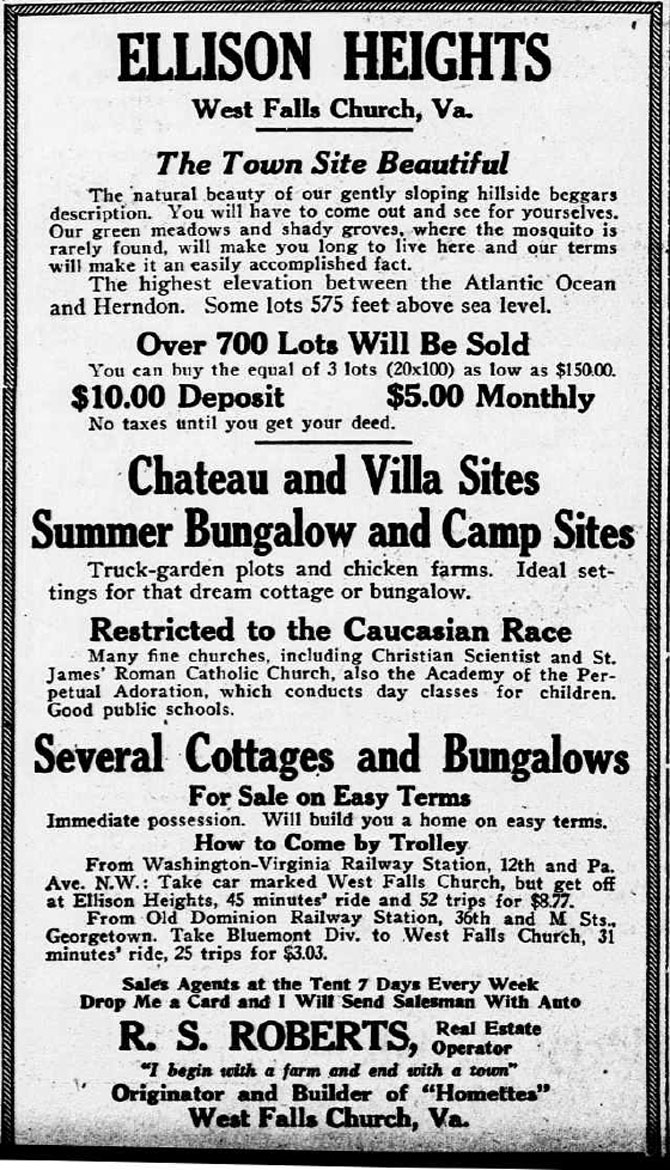

Ad touts: “Restricted to the Caucasian Race”

“We built a system for privileged whites to come to Fairfax County and covenants are part of that.”

— Dr. Krystyn Moon, University of Mary Washington history professor

Some real estate developers and others selling property in Northern Virginia from 1900 through the 1960s used race-based, restrictive covenants to maintain segregation, and Virginia’s state and local governments were enablers at times, Dr. Krystyn Moon, University of Mary Washington history professor told a packed room of 120 on August 27 at the Sherwood Regional Library.

In a talk titled “A History of Fairfax County’s Racial Covenants in Property Deeds,” she presented her research on the history and locations of racial covenants in Fairfax and Arlington counties and the cities of Alexandria, Fairfax and Falls Church. She has identified and geo-located racially-restrictive covenants across the region.

In introductory remarks, Lydia Lawrence, Nature Forward’s Director of Conservation, noted that with EMBARK’s redevelopment coming to U.S. 1, investments should be made “in an equitable way. We cannot treat something unless we understand the underlying cause,” she said, adding, “We must understand the intentional actions that shape the community in a particular way.”

Typical racial covenants were put into property deeds to prevent people “not of the Caucasian Race” from buying or occupying the land, Moon said. The covenants could have time limits or some would “run with the land,” extend beyond the original owner.

Some covenants restricted sales to Jewish people.

“We built a system for privileged whites to come to Fairfax County and covenants are part of that,” Moon maintained. She cited three practices that created housing inequity, “why things are the way they are”: racial covenants; land and aesthetic zoning; and limiting access to mortgages based on race.

Suburbanization and Jim Crow came together like a “perfect storm” in Northern Virginia, she asserted. Jim Crow refers to laws that legalized racial discrimination in the American South. In the 20th century, as roads and vehicles exploded and the state and federal governments encouraged road building, selling farmland to developers was more lucrative than farming and developers started converting farms to subdivisions. Also, in the 1940s, housing demand increased as people moved to the area for federal jobs.

In 1924, the National Association of Real Estate Boards adopted an “ethics” policy, declaring that Realtors should not introduce “into a neighborhood … members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood.”

Advertisements often included coded language, Moon said, terms like “fully restricted,” and “fully state of the art covenants,” which euphemized the practice as “modern.” Subdivision names today like “estates” or names of former plantations could be coded language as well, she suggested.

Covenants in Hybla Valley Farms

Moon highlighted developer V. Ward Boswell who in 1935 bought 125 acres along U.S. 1 next to the historically-Black Gum Springs community and built a subdivision called Hybla Valley Farms. She shared his 1935 deed for the lots which included this language: “No part of the said land shall be granted, leased, sold or conveyed to a person or persons of African descent, nor for the use and/or occupancy of a person or persons of African descent; and if any attempt to grant, lease, sell or convey any part of said land to a person or persons of African descent, the deed of said land shall revert to the grantor as though said deed or leased had not been made; and adjoining property owners may eject such person or persons of African descent from said property or cause them to be ejected by the proper actions in the courts of Virginia.”

Citing a 1970 census of Hybla Valley Farms and nearby communities that included property owners’ race, Moon concluded, “The restrictions had an impact.” A street today ending on the east side of U.S. 1 still bears Boswell’s name.

State Action

In 1912, the Virginia General Assembly passed legislation that allowed cities and towns to establish “segregation districts,” to designate specific neighborhoods for Black or White people. “A year after the maps were created, no Black individual or family could move into the white section of the town/city and vice versa,” she explained.

In 1924, the Virginia Racial Integrity Act categorized people as “colored” or white, “the most extreme in the U.S,” charged Moon. “This informed racial covenants in Fairfax County,” she contended, adding, “This room would be illegal in 1926.” In 1928, the Board of Supervisors created a process to review plats for developing subdivisions.

Removing Covenants Today

Several court decisions and the federal Fair Housing Act eventually made using racial covenants illegal. Some Northern Virginians sued to remove them and organized pickets and petitions to promote desegregation and fair housing. In 1968, the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors approved an “open occupancy” ordinance, designed to protect housing rights.

Though illegal, some covenants are still in legal records. In 2020, the General Assembly passed a law to provide a simplified process for homeowners to remove racial covenants from their chain of title. The state Supreme Court has created a form for landowners to prepare deeds at https://www.vacourts.gov/forms/circuit/cc1508.pdf.

Virginia Sen. Scott Surovell and Del. Paul Krizek will hold a workshop to help people who want to remove these covenants. “We intend to work with a local real estate closing company, title researchers and others to provide homeowners with the information and resources necessary to prepare and file these deeds in less than 30 minutes,” Surovell said.

Mount Vernon Supervisor Dan Storck and Franconia Supervisor Rodney Lusk attended the meeting and will propose that the Board of Supervisors remove or redact racial covenants language from County property deeds. “While the covenants are not applicable, we recognize the importance of removing this legacy,” Stork said.

Storck continued, “It was wonderful seeing so many residents engaged with our county and Mount Vernon history. I look forward to learning more and leading the county in updating our property deeds to remove or redact these racial covenants.”

Ron Chase said, “It was an excellent introduction, describing the obstacles African Americans face and so many nuances. This is an introduction to the trials and tribulations people experienced in our evolving culture.” Chase is president of the Gum Springs Historic Society and Museum.

Audrey Davis remarked, “The presentation shows us the many lessons we need to talk about. Most young people have no idea of this history. We still need to get some covenants removed.” Davis is Director of the African American History division of the Office of Historic Alexandria.

Moon’s book, “Proximity to Power: Rethinking Race and Place in Northern Virginia,” will be published by the University of North Carolina Press in 2025.

Cosponsors were Nature Forward, the South County Task Force, Fairfax NAACP, Mount Vernon Regional Historical Society and the Gum Springs Historical Society and Museum.

Information: https://documentingexclusion.org